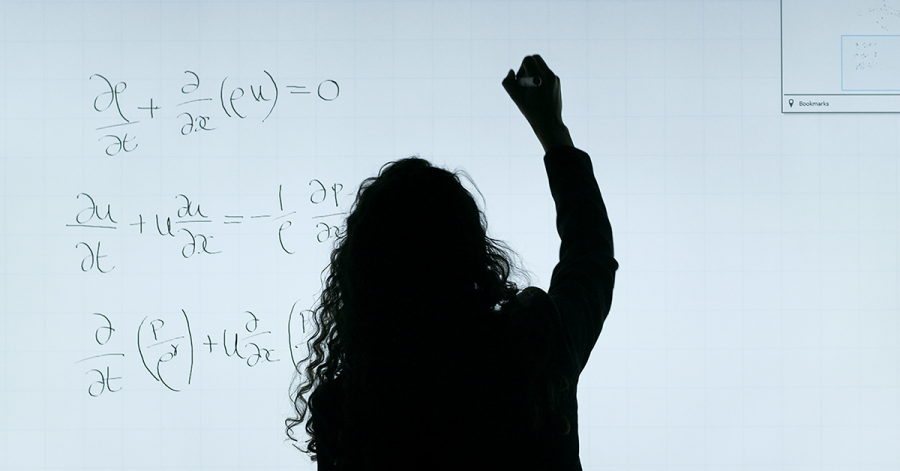

Flying with Both Wings: Women in STEM

“A bird cannot fly with one wing only. Human space flight cannot develop any further without the active participation of women.” Valentina Tereshkova, the first woman in space

When BBC shared an image of scientist Dr. Katie Bouman behind what appeared to be disc-like structures containing a lot of data, the world erupted.

Bouman’s algorithm had been instrumental in the process of creating the first ever image of a black hole. The accomplishment was monumental, but Bolman’s role exceeded that. Her picture became a global symbol of the power and potential of female scientists, but as well as being a moment to celebrate, it also turned the spotlight on women in the larger world of STEM and the challenges and barriers they often face compared to their male colleagues.

The inspirational quality of Bouman was, however, short-lived. Talk on forums and websites began disparaging her part in the algorithm, claiming that feminism was “inventing” scientists to take sole credit for team efforts. Despite Bouman’s statements honoring the team and collective work that went into that image, a small faction of the internet accused her of trivializing the efforts of her colleagues. The same people so adamant on equality never questioned why they believed she deserved less credit than her male counterparts.

Bouman’s story is only one among many. Women in STEM face similar battles every day, be it in schools, the workplace or at job interviews. According to UNESCO, only one-third of the world’s researchers are women, with far fewer holding senior positions, and creating a cycle where fewer women researchers have their work published, recognized, and funded. The numbers vary slightly on a regional basis, for example, in the European Union, 41% of all scientists are women. However, it still does not hide the fact that since its inception, only 19 of the 100 Nobel Prize laureates in STEM have been women.

A recent analysis of the nearly 3 million computer science papers published in the USA between 1970 and 2018 shows that with the existing numbers, an equal representation of the two genders would not be achieved until the next century.

Breaking the cycle

According to UNESCO, women account for only 28% of engineering graduates and 40% of computer science and informatics graduates, and this underrepresentation creates a dangerous loop whereby fewer women enter the STEM workforce, keeping employment ratios uneven. For example, in the US women make up 29% of the total STEM workforce but women make up only 3% of the industry’s CEO positions.

At Arçelik we are taking active steps to tackle women’s underrepresentation in STEM and working within the framework of UN’s Action Coalitions to encourage more women to enter the STEM workforce. We have made ambitious commitments to create a STEM talent pool that is rooted in equality and inclusivity along with programs designed to support women from the early stages in training and guide their trajectories towards leadership roles.

In accordance with the United Nation’s Action Coalition initiative, we have pledged to educate 100,000 young women across Turkey with the skills needed for a career in STEM. We will implement similar programs in Pakistan, Romania and South Africa to reduce the gender divide in R&D. We are also committing to support female entrepreneurs, by boosting the number of female sales representatives and investing nearly $4 million in female entrepreneur programs. Finally, we will also be increasing the number of female employees in STEM divisions (to 35%) across Arçelik’s global operations, as well as increasing the number of female technicians working at our authorized services.

These commitments serve a single purpose: to create an environment where women are presented with equal opportunities to excel within the field of STEM—from training to leadership.

One Katie Bouman story has the potential to create a hundred more.

Inspiration is key in creating careers. If we can facilitate a reality where young girls can imagine themselves working in STEM without any discouragement from their environments, we will be able to create a global community that is capable of progress and advancement.

For instance, the European Institute for Gender Equality estimates that having more women in STEM would increase the union’s GDP by €610 billion by 2050. Beyond the moral obligation to create an equitable environment, it is an economic reality that STEM careers—the key drivers of tomorrow’s economy—can only be carried to their full potential by an equal representation of all genders.

Our communities must remove the obstacles that keep women from achieving their potential in innovation, and invention. If we can facilitate a STEM industry that is rooted in principles of inclusivity and gender equality, our progress as the human species will be faster, greater, and more effective.

It’s time to let all Katies be Katies – at their best.